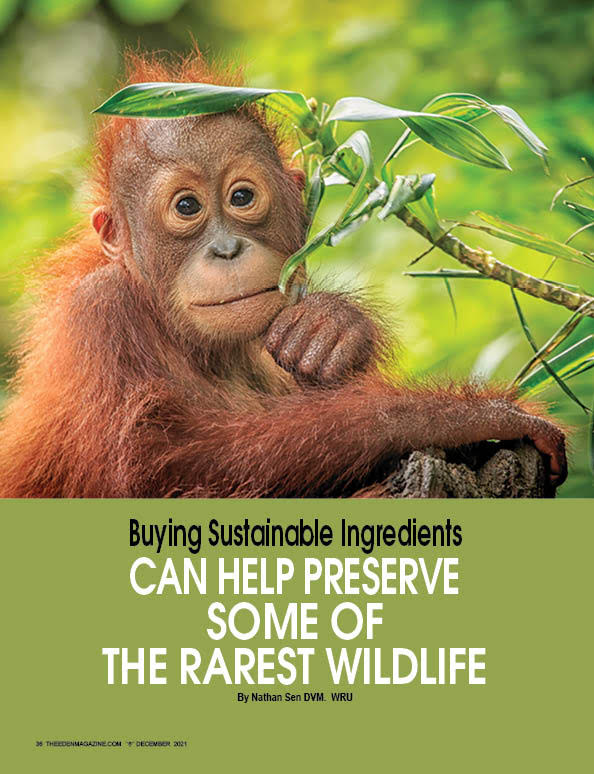

preserve some of the rarest wildlife By Nathan Sen DVM. WRU

Wildlife conservationist/veterinarian on the front lines says it is possible for orangutans, elephants, and monkeys to coexist with palm oil plantations

The island of Borneo, divided among Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia, is home to one of the world’s oldest rainforests. Borneo also produces about 80 percent of the world’s palm oil, a vegetable oil considered vital for global food security. In the U.S., palm oil is widely used in everything from snack foods and chocolate to cosmetics.

But palm oil production is also blamed for Borneo’s disappearing rainforest, destroying wildlife habitats, including those of the orangutan, which has become the face of a global anti-palm oil movement.

“In the past 50 years, things have gone from bad to worse. Efforts to preserve the area’s wildlife need to be ramped up,” stresses wildlife conservationist and veterinarian Nathan Sen, DVM, whose first job out of vet school involved rescuing orangutans.

Now, as manager of Malaysia’s Wildlife Rescue Unit and leader of the Sabah Wildlife Department’s new endangered species conservation unit, Sen is boots-on-the-ground in Borneo. He sees the sad realities.

Forest destruction is a rallying cry for the anti-palm movement. “Palm oil is called a golden crop. Its production is a valuable source of income, which has contributed to this worldwide ecological concern.

In some areas of the world, local farmers dreaming of a better livelihood have burned down forests and converted the land to oil palm plantations,” Sen explains.

But more recently, he sees glimmers of hope that may cause people to have a different perspective on the palm oil controversy.

The situation is shifting toward peaceful coexistence.

“The forest is one of Mother Earth’s greatest gifts to humans,” says Sen. “Palm oil can be produced more efficiently than other vegetable oils such as soy or rapeseed (canola).” It can also be produced responsibly. “By national law here in Malaysia, for example, all palm oil must be produced sustainably. There is also a strict ban on forest burning, as well as other initiatives to change palm oil production’s impact on our planet.

“One of the government’s initiatives is to stop the development of any new palm oil plantations and improve the production of our existing plantations. This is being done by introducing better trees that can produce more oil, and by improving the oil extraction process to increase the output, so the industry does not require more land,” Sen elaborates.

Another program involves creating wildlife reserve areas along riverbanks. “By not planting against the rivers, orangutans, elephants, and proboscis monkeys can now use the river’s edge for their habitat,” says Sen.

In the Malaysian parts of Borneo, the states of Sabah and Sarawak, there is a stable population of orangutans numbering between 11,000 and 13,000. The Malaysian wildlife and forestry authorities have taken the necessary measures, so now this wild population lives mostly inside a protected natural habitat area to thrive.

This strong governmental support of national wildlife conservation programs has a positive influence on the country’s palm oil farmers.

In the Malaysian parts of Borneo, the states of Sabah and Sarawak, there is a stable population of orangutans numbering between 11,000 and 13,000. The Malaysian wildlife and forestry authorities have taken the necessary measures, so now this wild population lives mostly in a protected natural habitat to thrive.

This strong governmental support of national wildlife conservation programs positively influences the country’s palm oil farmers.

“Ten years ago, farmers wanted to keep wildlife out of their plantations. I see a big change in that mentality,” Sen confirms. “More farmers now feel comfortable about coexisting with wildlife. They realize they share the forests with elephants and orangutans. They are allowing them to roam freely across their land. They are coming to understand that if we treat our wildlife with respect, the damage they may cause to the crop is quite negligible.”

He adds that he is very encouraged to see that orangutans are beginning to use Malaysia’s palm oil plantations as their habitat. It’s yet another sign that the country manages the delicate balance between caring for its wildlife and its economy.

Is the war on palm oil still justified?

If palm oil were to be banned, it would need to be replaced by less land-efficient crops. And as Malaysia has proven, palm oil production can be accomplished while protecting wildlife and forests.

But there is still much work to be done. “Many people still don’t realize that palm oil is the most sustainable choice. For sustainable palm oil production to expand globally, there must be a demand by the public. Be vocal about asking companies to source their palm oil from producers who are protecting the rainforests. And buy from companies that have already made that important commitment, such as Coca-Cola, Nestle, and Unilever,” recommends Sen. “While you may never see an orangutan in the wild, your food and personal care product purchases can help ensure these wonderful creatures have safe homes for generations to come.”