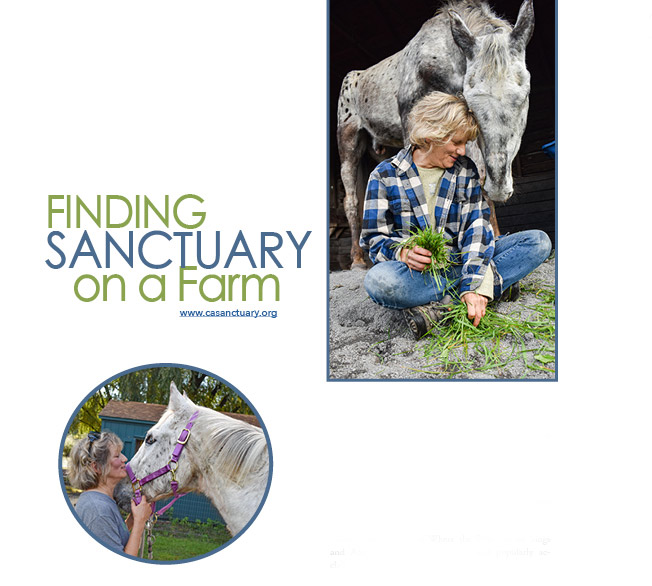

An interview with Kathy Stevens

After turning down an offer to lead a new charter high school, Kathy Stevens co-founded Catskill Animal Sanctuary in 2001. Her love of teaching, her belief that education has the power to transform, and her love of animals come together here. One of the world’s leading sanctuaries for farmed animals, Catskill has saved more than 5,000 non-human individuals through direct rescue — and exponentially more through programming that encourages humans to adopt veganism.

Kathy is the author of Where the Blind Horse Sings and Animal Camp, two critically and popularly acclaimed books about the work of Catskill Animal Sanctuary; she’s also a contributor to numerous books on animal sentience, animal rights, and sanctuary life, including the just released The Good It Promises, The Harm It Does: Critical Essays on Effective Altruism.

Kathy, tell me a little bit about your sanctuary.

We’re two hours north of Manhattan. We are a 150-acre sanctuary for farm animals: horses, cows, goats, sheep, ducks, pigs, chickens, turkeys, and even geese.

You must get a lot of calls. And you can only save so many. How does the process work?

You can only save as many as your resources allow- whether your resources are physical space, human capacity, or money. And any good sanctuary turns down many animals daily, particularly farm animals. Sadly there will never be a way to rescue our way out of this problem unless we deal with society’s unquestioned assumption that eating animals is okay. As long as we have that as our model, you could open a million sanctuaries tomorrow and not make a dent. So we take in as many as we can, based on urgency. We just welcomed two Texas Longhorn cattle yesterday from an animal hoarding situation. We will get the calls when a turkey farm downsizes, or animals come when people die, and the children don’t want animals. As we are in an economic downturn, our inbox fills up constantly with requests.

One of the things, and I don’t know if people ever asked you this, they asked me that all the time when people say to me there is a law in nature, where the bigger animal and so forth are eating the smaller animal. Would you say to those who justify this as eating those animals as part of the universal order?

There is an extraordinary difference. Animals eat other animals out of necessity. Whereas not only do we not need to eat animals in order to survive, but there’s decades of science and medicine that say people who eat a plant-based diet are far healthier than people who eat a meat and dairy-based diet- it’s one of the leading causes of all kinds of cancer and, and other health problems such as type two diabetes, heart disease, etc. Morally, there is a greater degree of suffering involved when you take a life when you grow it for the sole purpose of turning it into something consumable by humans. And that being, of course, wants their life as much as we want ours.

I would suggest that animals hunt other animals for necessity, whereas we have a choice. And as the ones on top, we have an ethical obligation to our fellow beings.

I agree with you. In fact, how is eating an animal part of a tradition?

Exactly. And if you don’t have that, will that tradition go away? That makes absolutely no sense to me.

When did you have your Aha Moment to do this?

I had been a high school English teacher for 10 years and was invited to be the principal of a new high school. I turned down the job, to my own shock! And I realized in doing so, that I was finished with that chapter of my life, and began soul searching to use a cliché. The two things I most care about are, on the one hand, teaching and learning and, on the other hand, animals, and I just started noodling on how I could put those together into a single entity that would take me through the next 30 or so years of my life.

So is this why you started a teaching sanctuary?

Yes, especially farm sanctuaries. Because nobody was doing the education piece in a way that felt so vital to me. Human beings consider themselves animal lovers. But if you press a person, they really mean that they love dogs and cats, or dogs and cats and rabbits, animals who share our homes. Nobody wakes up in the morning and says; I can’t wait to torture animals at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. It’s not intentional. We all have very rich emotional lives. We know that about our

chicken if we just had one for dinner last night. So I knew when we started from this assumption that people are good and love animals.

To have an environment in which farmed animals–so resilient, so forgiving–lick people’s faces and follow them around just like their dogs do and fall asleep in their laps: these animals are game changers! That’s what we’ve been facilitating for 22 years–the connections between loving animals and folks who “love animals” but still eat them.

The work you’re doing with the education, if people were in a sanctuary like yours, when the cow comes over and greets you and the turkeys sit on your lap, they ask themselves: can I really eat this creature?

We have hundreds of stories of people changing on the spot. One man in his 30s had just finished a tour, and he ran up, grabbed my forearms, and burst into tears. And he said I get it now. Tell me what to do. Sanctuaries are extremely powerful in the way that they allow people to confront the truth and the inconsistency in their behavior. You’d never eat a dog in this country. You’d never eat a cat.

How would you challenge someone asking: what’s the difference between me eating a hamburger right now? The animal has already been killed. What am I going to do, throw all this food away?

The answer is simple. It’s supply and demand. If we don’t buy it, if there’s no demand, there will be no supply. And wouldn’t that be an incredible challenge to have?

It is the most significant social change movement in history. And I also call it the most urgent because this planet is doomed unless and until a vast percentage of us stop eating animals.

I know you’re an author, and now you’ve written several books. Are you planning to continue to write books that could tell stories about going vegan or illustrate life in a sanctuary?

I hope to write more books. And I also have my podcast, “HERD AROUND THE BARN,” so my voice is still out there.

How can people visit your sanctuary? If they want to spend the night, can they stay in nearby places and make a day out of it?

Absolutely. We are in the Hudson Valley. We have a fully restored beautiful bed and breakfast on the property. So we’re open that’s open year round. And people can book that on our website. We also are open on weekends for tours. We’re open year-round, seven days a week for, for private tours by appointment.

For more information on Kathy’s work and her Sanctuary, visit: https://casanctuary.org/

At Catskill Animal Sanctuary, we’re deeply connected to the 150 acres that have been our home for the past 21 years: warm pastures where contented cows sunbathe, ponds where ducks swim for hours, fields for horses to run and roll in, and graceful willows dipping their branches low for goats to nibble on.

Our vanishing trees

The consequences of climate change are being felt globally, with climate refugees (often already vulnerable people) at the forefront of this emergency. While we are more geographically fortunate than many, we, too, are experiencing changes at our Hudson Valley refuge that can’t be chalked up to the vicissitudes of “weather.”

As the planet warms, microbursts, which can cause devastating damage, are frequently increasing— last year alone, the sanctuary lost 22 trees in a single microburst. In February 2022, we survived an “Armageddon-like” ice storm, which downed dozens of trees, tore off large limbs, and damaged fences, vehicles, and a small barn—many large branches dangled by a thread, threatening the safety of humans and animals.

Our trees’ loss, root systems, and torrential rainfall have led to dramatic topsoil erosion. The erosion further imperils our trees as their roots are exposed, losing vital grazing in our pastures. Two of our more extensive fields are no longer safe for our larger and more elderly animals due to the exposure of vast swaths of rock faces that were covered in soil and grass just a few years ago. Finally, as we lose more trees, we lose vital shade. Our soil health deteriorates further.

The most dangerous idea

One of the most dangerous ideas still touted by a tiny but vocal minority driven by a political agenda is that climate change is “fake.” But rising sea levels, extreme weather events, water scarcity, wildlife habitat loss, and global food scarcity remain facts, irrespective of our beliefs, emotions, or political affiliations. And as the fate of the planet and our very existence upon it is at stake, our thoughts and hearts turn to what we can do—as an organization and as individuals—to build a livable future before it’s too late.

Corporations and politicians have the will to take bold action: the former is too driven by the bottom line; the latter is too beholden to the former. So, as has been the case with every other social change movement throughout history, it is up to us—one person, one household, one community at a time—to make changes that will drive corporate and political power to act. And we must make those changes now. The most recent report from the United Nations issued a “Code Red” for the planet, laying out why bold and urgent action is imperative.

What, then, can we do?

A recent climate study showed that a global shift to a plant-based food system over the course of 15 years would “substantially alter the trajectory of global warming,” With animal agriculture one of the leading contributors to global greenhouse gas emissions, this shift could help balance out emissions from other sectors such as transportation. Allowing land to rewild, rather than using over a quarter of the Earth’s surface for grazing “food animals,” would create vital carbon sinks, tangibly reducing the amount of carbon entering the atmosphere. Since growing animals to feed humans is a massive contributor to greenhouse gas emissions—a root cause of the warming of our planet that causes climate change—this shift is vital. And it is urgent.

For example, among the greenhouse gasses emitted by “food animals” is methane, which causes a 25x greater impact on the climate than carbon dioxide. Methane is created from the natural digestive processes of cows, pigs, goats, and sheep and is found in large quantities in their manure. According to the EPA, the agriculture industry is the second largest source of methane in the United States. To help combat these emissions, rewilding – a progressive conservation practice that allows nature to “heal itself” after being deforested and used for grazing or the growth of crops to feed animals – can create forests and other “carbon sinks” that absorb tremendous amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses from the atmosphere.

What can individuals who have no control over land use do? Each of us can make a tremendous difference by reducing or eliminating our consumption of animal products. While it may seem daunting, we can make this shift: We know because we’ve helped thousands of folks do it through our Compassionate Cuisine program, which has won awards for demonstrating how accessible and delicious vegan food can be. Our humane education program changes live by introducing farmed animals to visitors (both in-person and virtually) and sharing their heart-opening stories. Sometimes, the humans step back and allow the animals to work their magic on unsuspecting guests. Epiphanies happen at farmed animal sanctuaries.

Mend what is within your reach

“Ours is not the task of fixing the entire world at once,” writes psychoanalyst and author Clarissa Pinkola Estés, “but of stretching out to mend the part of the world that is within our reach.” Today, tomorrow, and as long as possible, mend what is within your reach.