By Dina Morrone

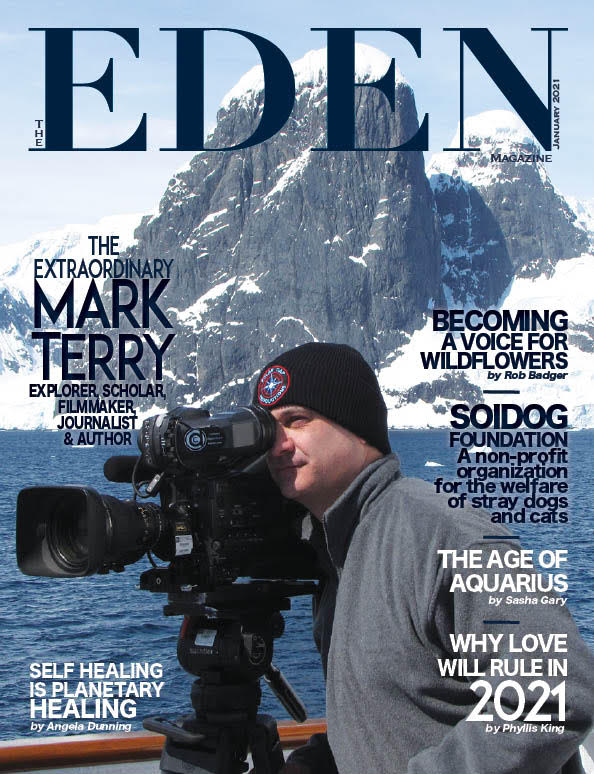

Canadian, Dr. Mark Terry, is an explorer, filmmaker, scholar, journalist, and author who focuses mostly on climate change. His documentary The Antarctica Challenge: A Global Warning made such an impact that The United Nations invited him to show the film to world leaders. He has been honored with a Diamond Jubilee Medal, the Sustainability Award Leadership Award, and Audience Choice Awards at the American Conservation Film Festival for his films The Antarctica Challenge: A Global Warning and The Polar Explorer.

Dr. Terry is a Research Fellow with the Dahdaleh Institute for Global Health Research at York University in Toronto. He also teaches in the Faculty of Environmental and Urban Change at York and in the Faculty of Arts at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, both in Canada. He has worked throughout the global Arctic, serving as the Scientist-in-Residence on a circumnavigation of Iceland in 2018, making the first documented film of a crossing of the Northwest Passage, The Polar Explorer, and lecturing at universities around the world, including St. Petersburg and Moscow, Russia. He has also worked in Antarctica documenting the research of the British Antarctic Survey and the National Antarctic Scientific Center of Ukraine. For the United Nations, he serves as the Executive Director of the Youth Climate Report, a film program for youth.

On November 27, 2020, Dr. Terry was inducted as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. The society honors scholars, scientists, and artists elected by their peers as the very best in their respective fields. The inductees are individuals from all branches of learning who have made extraordinary contributions in the humanities, sciences, the arts, and in their Canadian public life.

Congratulations, to Dr. Terry, on his remarkable career! It’s a real honor for The Eden Magazine to feature him in this January 2021 issue.

Some boys say they want to grow up to be a firefighter, a doctor, or a hockey player. As a young boy, what did you want to be?

Not many people actually become what they say they want to be “when they grow up”, but I did. I always wanted to be an explorer, as far back as I can remember. As a young child, I went to the park and dug a hole under the concrete bleachers to get inside. It was a place “no-one had been before” – the essence of exploration. I called this place my “fort” and would go there with a sandwich and have lunch there. There was a six-inch slot that I could peek through and watch the world go by. I had similar forts under the stairs at home and on the roof at school. I deeply admired people like Sir Edmund Hilary and Sir Ernest Shackleton for finding their own “forts” where “no-one had ever been before”. I like to say that “the destination of discovery begins with a journey of exploration”.

Please tell us what it was like growing up in Toronto, Canada?

It was a very pleasant time growing up in Toronto in the ‘60s and ‘70s. We lived in a neighborhood known as East York, Canada’s only borough. Many Italian immigrants lived here, so most of my childhood friends were Italian, and many of them remain my adulthood friends today. Since it was a time before computers, we spent our free time either playing sports or going to the cinema for 35 cents to watch three first-run Hollywood movies back-to-back. I spent my Saturdays doing that and the rest of the time playing hockey in the winter and tennis in the summer. On TV, we watched with curiosity the significant events of the day – the Vietnam War, the Kennedy assassinations, the Charles Manson murders, the Kent State shootings, the race riots – from a safe distance here in Canada.

When did you first realize you were passionate about the environment and climate change? And what did you do at that point to take action?

I guess I was always passionate about the environment without knowing that I was. It was just a way of life for me to prefer to spend a summer at the lake, hike through the Don Valley, swim in Lake Ontario, and play hockey in the freezing cold winters at Dieppe Park. This was second “nature” to me as it was with most of my friends and family. My advocacy for the environment was formalized in 2008 when I decided to make the documentary film The Antarctica Challenge: A Global Warning to report on International Polar Year research in Antarctica. I realized that no-one else was going to do this – not because they didn’t want to, but because it’s painfully challenging to arrange passage there and prohibitively expensive for most independent filmmakers. I was determined to go at the age of 50, as I believed this was significant research that the world needed to know as we began to become familiar with the term “climate change”. Having made the film, I was comfortable with spreading the news it presented to the public through film festivals, television broadcasts, and home video sales. What I didn’t count on was the interest the United Nations had in this project. That began my relationship with the UN as a media provider that continues to this day.

As a professor, you play an essential role in educating future documentary filmmakers focusing on the environment. What are you learning from your students that surprises you and impresses you?

I am surprised by the extent of the knowledge of all environmental issues – not just climate change – that today’s students have. Clearly, they recognize this as the global issue of their lives and their future, so they are deeply committed to learning about the problems and finding viable solutions. What surprises me in the classroom is their comfort, skill, and talent with geomedia. I teach them a remediation of the documentary film – the Geo-Doc – a multilinear, interactive, database documentary film project presented on a platform of a Geographic Information System map of the world. They end up teaching me new techniques, functions, methods, and approaches that enhance the technology and make it more robust as an effective communications tool for environmental policymakers.

Of all the films you have worked on, which project taught you the most about yourself and why?

I’d have to say The Antarctica Challenge. It taught me that I can indeed do anything as I managed to complete a film that so many said couldn’t be done. And then to have that film go on to become one of the first films ever, specifically invited by the United Nations to serve as a data delivery system for policymakers. This awoke in me a realization that there is a different path to activism, one that is more direct than protests and letter-writing campaigns. This approach involved the policymaker as a collaborator. They were revealed to me as co-operative colleagues embracing progressive change, not stubborn enemies resisting it. To see the policy process incorporating my films forged in me a commitment to continue to provide the visible evidence the policymaker needs to assist in the creation of effective policy, a visual tool that provides additional context to the scientific papers they usually use as resource material.

Not many people can say they are a polar explorer. You have had quite an adventurous life and seen places most people only dream of seeing. Please tell us one of the places you are still hoping to visit? Explore? Vacation?

I’d like to explore the European Arctic, especially Russia’s far north. I’d like to compare it with what I have experienced in the North American Arctic of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. I did visit the University of the Peoples of the North in Saint Petersburg, Russia. I was fascinated by the variety of cultures among the Indigenous people there. I was also impressed by the university they had built for themselves and the unique curricula you’re not likely to see in any other university. As far as vacation destinations go, my favourite place to relax and recharge is the Bahamas, the antithesis of the polar regions.

I am in awe of your work as a documentary filmmaker. Not just with the size and scope of your projects, but more importantly, the fact that you make breathtakingly beautiful films that enlighten, educate, and entertain. How do you choose which projects you want to pursue?

There are two motivating factors in my decisions to make a documentary film. The first is it must excite me. It must entice the explorer in me. I want to go to a place that not only I haven’t been to before, but also a place that few people have ever been to before. By selecting such a place, I

will be able to share images of far-off lands that my audiences can see, perhaps for the only time in their lives. The second consideration is the United Nations. They have come to expect objective reports of environmental research in my films provided by the testimony of embedded scientists working in these places. Knowing that my films assist the policymaker in advancing solutions to global issues like climate change makes my work a rewarding vocation, a calling.

The Changing Face of Iceland is your latest documentary – the third film in your Polar Climate Change documentaries’ trilogy. Please tell our readers about this new film and also where and when they can see it.

The Changing Face of Iceland is the third film in my polar trilogy (the other two being The Antarctica Challenge and The Polar Explorer). In this film, we look at the impact climate change has had and is having on this island nation at the edge of the Arctic Circle. Glacier decline is a genuine concern at both ends of the earth, but here there is an additional threat: volcanic activity. As glaciers melt in Iceland, they relieve the pressure on underground magma rivers. This flowing lava can now move more freely with the ice cap removed and this is feared to lead to substantial eruptions in the near future. We also feature an interview with Iceland’s first female prime minister, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, who addresses the changes Iceland is going through with an encouraging and positive perspective. The film also features some of the most spectacular drone footage and breathtaking scenic vistas you’ll ever see on film.

More and more people worldwide are finally jumping on board with a mission to stop global warming. For those who have still not joined the movement, how can they be convinced to do so? And what can the average person do today to help with our current global environmental crisis?

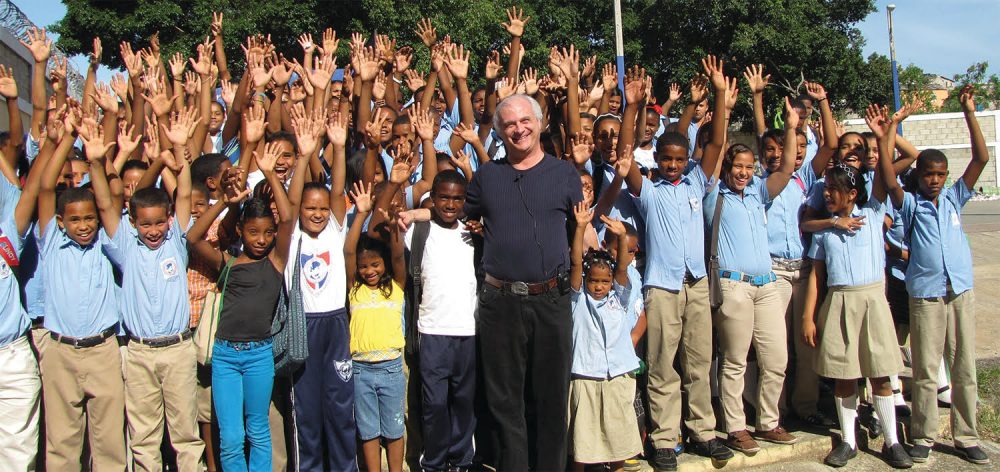

On a grand scale, people can start to adopt significant changes in their lifestyles with respect to energy. Electric cars are not only becoming commonplace but actually affordable as well. Tesla is set to announce a $25,000 fully electric car next year. For homeowners, look into going off the grid and replacing your electrical energy needs with solar power. You’d be surprised to learn that many governments (municipal, state/provincial, and federal) have incentive programs that provide grants for making the switch. More surprising is that many people using solar power today produce an excess of energy that they can sell back to the conventional grid. Not only does your electric bill go down, but you can make money at the same time. On a small scale, the average person can support projects intended to showcase research in climate-based solutions like the Youth Climate Report, a not-for-profit organization supported by four UN agencies (UNFCCC, UNEP, UNDP, and UNESCO). This interactive Geo-Doc film project currently showcases more than 450 documentary short videos produced by the global community of youth on all seven continents. I curate this project and train young environmental filmmakers from around the world through a program called the Planetary Health Film Lab. You can support this initiative with a secure PayPal donation here: http://youthclimatereport.org/donations. For those looking to be more involved and to associate their business with this UN program, sponsorship information is available here: http://youthclimatereport.org/sponsorships. For general information on the Youth Climate Report project, please visit this website: https://unescochair.info.yorku.ca/networks/youth-climate-report.

Please tell our readers about the impact the Montreal Protocol has had (initially signed in 1987) in stopping the use of substances that deplete the ozone layer?

The Montreal Protocol is arguably the most successful international environmental policy to date. It marked the first time every nation on earth collectively came together to sign a single piece of legislation. This happened again, of course, with the Paris climate summit in 2015 until the US decided to opt-out when Trump took office. The Montreal Protocol effectively banned ozone-depleting substances such as Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) through a phasing-out process that all the countries in the world agreed to. Since then, the world has seen CFCs drop by as much as 98% in the atmosphere. This has allowed the ozone holes over the poles to repair themselves. In 2019, we saw the smallest ozone hole since 1982; however, on September 20, 2020, the annual ozone hole reached its peak area at 24.8 million square kilometers (9.6 million square miles), roughly three times the size of the continental United States. Why Antarctica’s ozone hole went from near-complete recovery to one of the biggest declines in just one year is not yet known, and this surprising turn of events has thrown NASA’s previous models indicating complete recovery by 2040 right out the window.

What do you do in your free time when you are not working, traveling, or exploring?

Well, I could say that when I’m not doing those things, I’m thinking about doing those things, but seriously, my free time is minimal, and I enjoy reading and watching TV like everyone else. I will often play with the digital scrapbook known as Facebook as well. I particularly like visits with my children, their partners, and my grandson Nico who will turn three in January.

Of all your significant accomplishments, and you’ve had many, and more to come, please tell us what makes you the proudest?

The films I’ve made hold a special place in my heart as they have been recognized for excellence worldwide and opened a direct path to contributing to global environmental policy creation for me with the United Nations. But I am particularly proud of my academic achievements. As the oldest graduate in my class, I realize that returning to school to earn a Ph.D. is not something most 60-year-olds do. With this degree, I now have the credentials to teach others what I know and what I have experienced, to encourage and inspire them to pick up my mantle and run with it. My knowledge base is not just academically theoretical in nature, but professionally practical as well, informed by my career as a documentary film practitioner. Ultimately, this combination of theory and practice provides a more well-rounded education for the student in the areas of documentary film production, social activism, and environmental advocacy. I am also very proud of my book, The Geo-Doc: Geomedia, Documentary Film, and Social Change, published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2020. This is my first book. It represents an extension of my dissertation and a summary of my career as an environmental filmmaker. But honestly, what makes me the proudest are my two remarkable children, Herb and Mary Anne.

Among your many published books, your latest, released in July 2020, is entitled Pandemic Poetry. At what point during the pandemic did you decide you had to write this book? And please tell us a little bit about the book?

Pandemic Poetry was written in July 2020 following four months of restricted isolation. During this time, I was able to reflect on this unprecedented global event in the lives of almost everyone on the planet. Much was being written about our reactions to the pandemic and our various difficulties and challenges with what was fast becoming known as the “new normal,” and I sensed much despair and hopelessness as people I knew lost loved ones. While a foreseeable end to the pandemic either by a vaccine or by nature was not evident, I realized hope was in short supply, so I decided to explore areas where I might find encouragement for the troubled masses. I could have written a book of prose, a journalistic article, or an academic paper on this subject, but I believed the vehicle of poetry would reach more people in a more accessible manner. The poems touch on many of our experiences during this dark time: the Black Lives Matter protests; the missed personal and joyful experiences of holidays: Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, Memorial Day, and birthdays; the reclamation of nature over our anthropogenic footprint; and the perspective of wildlife now comfortably walking our city streets. All subjects present an objective observance with an underlying message that this, too, shall pass and that life as we used to know it will one day return.

What’s next for you, Mark?

I plan to expand the training workshop for young filmmakers I’ve developed called the Planetary Health Film Lab to include the Indigenous youth of the Circumpolar Arctic. This project will provide the theoretical approaches and the practical skills for creating documentary short films aimed at informing and influencing the environmental policymakers of the United Nations. I’m excited about amplifying the voices of this under-represented global community at the annual UN climate summits. I am also eager to explore new horizons, as always, expanding my experiential education so I may share it with others in my never-ending efforts to make the world a better place for all of us.

http://youthclimatereport.org/donations

http://youthclimatereport.org/sponsorship

https://unescochair.info.yorku.ca/networks/youth-climate-report

Comments