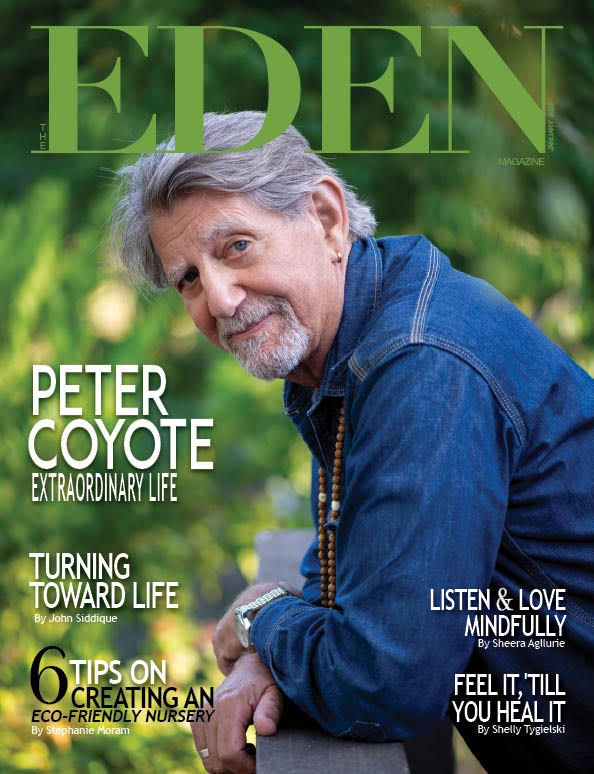

Peter Coyote

By Dina Morrone

Welcome to the world of Peter Coyote, a multi-award-winning actor, author, director, screenwriter, narrator, and activist, opens up to us at The Eden Magazine about the many aspects of his extraordinary life, from the glamour of Hollywood to the humble life of a Buddhist Priest.

How did your childhood growing up on the East Coast influence the life choices you made?

I was lucky enough to grow up in both an urban and a rural environment. My parents were sophisticated people who loved theater and music and had many artist friends. My dad’s great passion was raising Charolais cattle (which he and his partner smuggled across the Rio Grande by painting black spots on them to disguise them as Holsteins) to avoid the prohibitions on them created by the Angus and Hereford lobbies.

Read Our Magazine…

I was working on the ranch at ten years old under the foreman, and it was the best thing my dad ever did for me. It got me out from under his thumb, and I learned about people who were never going to go to college—for whom life was simply work. They did everything at the speed they did anything—hammering a nail, throwing a bale, smoking, or drinking a beer. I learned what brilliant problem solvers they were and never forgot rural people.

On my mother’s side, there were a lot of social activists and communists in our family—labor organizers, teachers, people who wouldn’t overthrow a pushcart but were trying to get a square deal for working people. I never forgot their example or the way my government lied about them. I saw grown men and women in tears in my living room during the McCarthy period, broken by the same kind of rats currently trying to overthrow our electoral process. I never forgot them, and I’ll never stop struggling to protect democracy.

Not sure if it’s an East Coast or West Coast thing, but when my family lost all our money, I lost my beloved ranch and wound up in the West, and I’ve been here so long, I’m a Westerner. But that’s a whole other topic.

What was it that first inspired you to become an actor? What were the first steps you took towards pursuing this career path?

Well, the truth was that I wasn’t inspired to be an actor. I was a poet in college–part of the black turtleneck, Camel cigarette crew. And one day, in the student union, the drama teacher, half in the bag, a wonderful man named Ned Donahoe, dropped into the poet’s corner, and addressing me said, in a stentorian voice, “I’ll bet it’s never occurred to you that theater is a dialogue on issues of critical importance played out before an audience.” I was stunned and said. “No, to be honest, it hadn’t occurred to me.”

He challenged me to come audition for his theater company. I did, and he accepted me, and he put together a group of really talented people. He wasn’t very patient with ‘academic’ theater. “The basketball coach uses his first string. Why should I settle?” Anyway, I did two shows a year for four years, inspired by him. And after I graduated, I went to San Francisco to pursue a Master’s in Creative Writing, but I joined a kind of moribund theater, the remnants of a company taken to NY to start Lincoln Center, which took the best actors with them. I stayed in that company for a year or so, but it wasn’t a good fit.

Then one day, I passed our smaller theater we were renting to a company called The San Francisco Mime Troupe. They had their lobby festooned with photos of crazy-looking commedia dell’arte performances. (Think Punch and Judy with people.) They also had two of the most astounding looking women I’d ever seen, Kay Hayward and Sandy Archer. I auditioned for them the next day, was accepted, and given all the responsibility I could handle–including directing the first national tour of a very dangerous show called The Minstrel Show, which was used to expose the racism of minstrel shows. We were arrested multiple times on the tour when people realized this was a story that could have been written by Malcolm X. Anyway, I stayed there for a couple of years and dropped out and into the counterculture and co-founded a group called the Diggers. I forgot all about ‘art’ per se in my efforts to imagine a culture better than the one I’d inherited. It was only a decade and a half later, after my dad died broke, I was a single father of a daughter, working for the Governor of California and I had great success at that job, which convinced me that I didn’t need to just think of myself in terms of the counterculture. I had helped create and sell the policies that swelled our budget from $1 million to $16 million a year, made friends and relationships with conservative Senators and Congresspeople, and won their respect. So, I decided to try “the Big Board”—the movies. I gave myself five years, figuring if it didn’t work out, at least I wouldn’t die with the ‘what-ifs.” But I got lucky.

At what point in life did you choose the path of Buddhism and why. Is this something you searched out on your own?

Well, I’ve told this story in both my books, Sleeping Where I Fall and The Rainman’s Third Cure, so I don’t want to talk it to death. My childhood was pretty troubled, and in my early teens, I began reading the Beats—grownups as critical of the current times as I was, only educated and far more literate. They were all involved with Buddhism and talked about it so much I began reading up on it. The idea of Enlightenment was the perfect carrot to swing in front of the nose of a horse-stupid, overweight adolescent who was cripplingly shy around girls. The idea of it stayed on the back burner somewhere in my mind, and after ten years of heroin and too many other drugs, and with a child to look after, I realized I had to get my life together. I was chasing a woman (who I later married) who was a serious Zen student, and so I began sitting at the San Francisco Zen Center (AND going to therapy), and it stuck.

In 2015 you were ordained a Zen priest. Please tell us where this happened and a little bit about the experience of that moment.

By 2012, I’d been studying Zen for nearly forty years. My teacher was involved in a three-year priest’s training program and asked me to take it. I told him I’d never be ordained, but he said it didn’t matter, just see what I learned, so I signed up. I was so impressed by the caliber of the people taking the training that by the time it ended, I really wanted to up my commitment and game, and so I agreed to be ordained.

Ceremonies are interesting because they actually change you when they’re well done. It took about a month after I was ordained before I began realizing I knew things I hadn’t understood I’d known. My teacher had predicted that this would happen, that the “lineage would begin to speak through me,” and it did. About five years after that, I was transmitted—which means my teacher invested me with the authority to be independent and ordain my own priests. After that, I vowed not to teach publicly for five years. That period was up during the pandemic, and I began doing public dharma talks.

For our readers, who don’t practice Buddhism or those just now embarking on a path of Buddhism, please speak to them about the beauty of this practice, what to expect, and what their focus should be in the beginning.

First of all, the Buddha was a man—a normal man with extraordinary logical and analytical powers. Everything he taught me is available to any living human. It’s not in conflict with any religion. It is a practice, a way of living, in which we try to model the Buddha’s behavior.

The Buddha had two basic insights: 1) Dependent Origination, which means everything depends on other things for its existence. Nothing from an atom to an elephant stands single and alone. This is as true for the awareness we call our “self” as it is for everything else. Because nothing exists singly, Buddhists describe things as ’empty’ of self. We would not be here without sunlight, water, oxygen, pollinating insects, microbes in the soil to nourish our food, etc. What this means by implication is that we are not “fixed” in a given way. The thing we refer to inside us is an awareness without a physical referent like an organ. That means that most of our behaviors are either inherited or habitual, and we have the freedom to counter them.

The other “ground” of existence he pointed out was 2) Nirvana. Because everything is empty, in the next moment, we can choose to do things completely differently and be free. To do that, we need to learn to drop our habitual responses to events and what arises in the mind, and exists with a kind of interior stillness, which we practice through meditation. From that stillness (as opposed to our normal egocentric perceptions), we can see things as they actually are and respond appropriately. That’s the short course.

Please tell our readers a little bit about Project Coyote, what they can do to get involved, donate, and where they can go to learn more about this very worthy cause.

Project Coyote is a very worthwhile project that teaches people to understand and live with apex predators. There are many things we do. We have taught local farmers how to protect their livestock with guard dogs and fences without having to set traps and use poison, which they really appreciate. We have been successful in many states at stopping “sport-killing” contests, where people will compete to see how many coyotes, lynx, or badgers they can kill in a weekend. It destroys an environmental niche, is ignorant in the extreme to think that we humans get to define what deserves to live and what doesn’t. You can find Project Coyote at: https://www.projectcoyote.org/, and I hope that readers will check it out. We know enough now to know that when we weaken environmental links, very destructive things occur. A coyote eats about 2,000 rats a year, so you can take your choice as to which you’d rather live with. We saved Marin Country over $250,000 a year by ending the poisoning and trapping of predators, and the farmers are greatly relieved and love the new systems we taught them.

Your most recent book, Tongue of a Crow, is your first poetry collection. Tongue of a Crow is a very intriguing title. What motivated you to write this book of poems at this particular time? And can you share a little bit about why you chose this title?

Well, it’s a line from a poem in the book. But on a deeper level, it means opening ourselves to what nature has to tell us. There used to be a superstition that if you slit the tongue of a crow, it could speak English. In fact, they can imitate English words without slitting their tongue. I feed twenty crows every day and call them in when I’m throwing out shelled peanuts. They know what the word breakfast means and come running.

As an award-winning voiceover artist, your voice is one of the most recognized voices. Today, many are trying to break into that field. How did you break into this line of work, and what is it about working behind a microphone that gives you the greatest satisfaction?

When the counterculture ended, I wound up in San Francisco, broke, and the idea of maybe getting a few ads occurred to me. I made a CD with about ten characters talking about what a miserable person Peter Coyote was in various dialects and accents, kind of showing off my wares. It was very funny. I took it around to every ad agency in San Francisco. And before long, I was making triple scale. Then, after some success in films, I was put into the “celebrity voiceover” category, where it’s kind of fun for people to recognize the voice of the actor speaking, but you’re not really endorsing the product. As I got better known, and after I met Ken Burns, I pretty much stopped doing advertisements and concentrated on documentaries–many of which I do for free to help out worthy causes I believe in.

What would you like to say to young college students today about the power of their own voice, their actions, and activism?

The most important thing I could say is KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE. Too many protests today aim at the wrong target and become campaign videos for people you wouldn’t agree with. A protest is a CEREMONY. It’s an invitation to a better world, not an opportunity to express your anger and outrage. If you think back to the earliest Civil Rights demonstrators, look at them carefully. They dressed as if they were going to church. They never raised their voices, except in song. They were disciplined, and the accumulation of that behavior set them apart from the bigots beating and spitting at them.

Too many protests today are aimed at the police or legislators. It’s the wrong audience. The only audience that counts is the mass of people living between the Alleghenies and the Sierras. They are watching, trying to determine who they trust and whose side they’ll be on. Disrespectful behavior, screaming, destruction of property turns them off. That’s what elected Nixon and Reagan after the Sixties. Here are four things I think should be considered in any protest.

1) Dress as well as you can. It’s hard to peg people as terrorists when they’re put together.

2) Have MONITORS in yellow vests scanning the crowd. At the first sign of trouble, they blow WHISTLES, and all the real protestors sit down! Let the police take out their aggression on the provocateurs and others destroying the neighborhood.

3) Be silent. Let signs do your talking, and let America see your discipline and self-control.

4) Go home at night. You can’t tell the cops from the killers in the dark. Leave and come back the next day, rested, fed, and with the energy to remain disciplined.

With regards to diet, what is one food item you crave and what food item will absolutely not eat and have cut out of your diet?

I always seem to crave noodles, and I crave bacon, but I rarely eat it because pigs are so badly treated in commercial farming. You can buy a cow that was petted to death at Whole Foods (graded at five on a care scale). You can’t buy a pig above a two. So occasionally, if a local farmer raises pigs in a nice way and butchers them himself, I’m okay with a little bacon as a scarce rarity. I used to raise pigs, and I know how sensitive and intelligent they are.I don’t eat any red meat anymore. It’s too environmentally expensive, thousands of acres of plant food dedicated to cattle feed, the incredible amounts of methane they produce (second leading contributor to carbon in the atmosphere), and also the cruelty of these timid, basically wild, curious animals.

I don’t eat tuna because it’s overfished, and I don’t eat octopus after seeing My Octopus Teacher.

What does a day in the life of Peter Coyote look like?

I get up at 5:30 or 6:00 and meditate. Then, if I have memorial services or something to do, I perform them.

Walk and feed my dogs

Take a cup of coffee and watch the news

Try to write for two or three hours (or fulfill work

appointments)

Chores after lunch

Walk the dogs around five, feed ’em

Eat around six while I watch the news

Then I turn my brain off and watch some TV series: Succession, Rust, Doc Martin, The Knick, A French Village. I’m all over the place.

Try to practice the guitar every day (fail)

And get enough sleep (fail)

Special Thanks to:

Peter Coyote

Cheri Head

Photography by: Stephanie Mohan

Comments