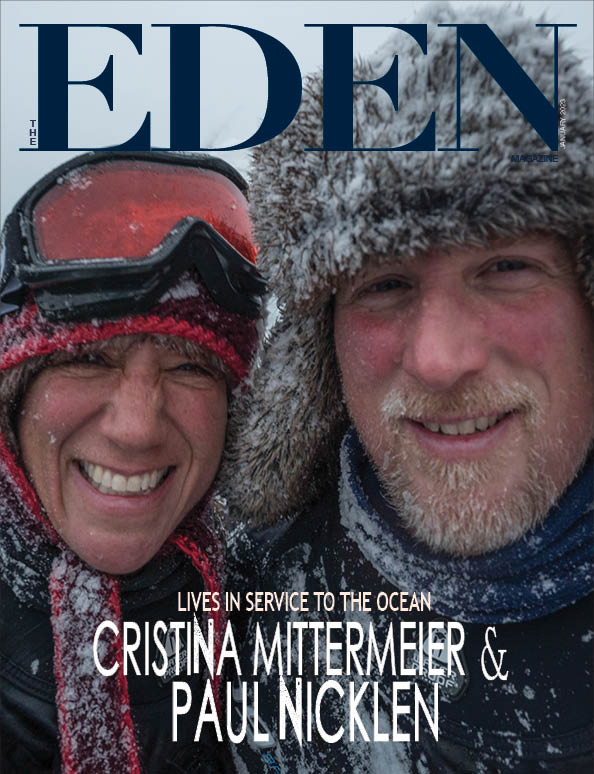

Paul Nicklen & Cristina Mittermeier

Interview by Dina Morrone

My interview with Cristina and Paul has been a highlight of 2022. They are so enthusiastic and devoted to sharing their stories and vast knowledge with the world through photography and images. Hearing them speak was powerful, and I must admit, I was quite moved. Their passion for their work and love for the planet and all sentient beings is on another level. And their commitment to ensuring future generations will inherit healthy oceans is an absolute must and a priority for them!

I encourage all our readers to please get involved. Whether it’s a signature on a petition, a financial donation or a contribution, or to learn more about what you can do to make a difference, please share this interview, or visit SeaLegacy.org.

Read Our Magazine…

“This is our last stand for our planet – this is it! If we can’t get this right now, what will we leave for future generations? I think half the species on the planet are already dead through extinction, and we’re facing the next big extinction.” ~ Paul Nicklen

When did you first pick up a camera, and what was your subject?

Cristina The truth is, I didn’t pick up a camera until I was in my mid-20s. I was already a mother and married, and I picked up a camera only by accident.

Paul: Growing up in Baffin Island, my mom had a dark room inside one of our closets where we kept all our dried food because our groceries came once a year by ship. I was always in awe of my mother, but it wasn’t until I was 16 that she let me use her Pentax K1000, a very manual camera. I never knew that the world of becoming a photographer would be open to me. I started shooting underwater for the first time when I was 19 years old when I went to the University of Victoria.

Cristina: Some photographers are enamored with the equipment and have stories about their parents giving them Brownie cameras. I’ve always been artistic and love so many aspects of art, including writing, painting, and music, and I didn’t know that I would be good with a camera. It was a total surprise to realize that you can create images and imagine images before you even shoot.

Paul: The thing about photography is that it’s so subjective. I’m not able to put any of my work on the wall because I’m too critical and pick it apart. With photography, it’s a journey. It’s not like a sport where you can say, “I’ve got the fastest time.”

I love the moments with the animals and nature and being lost in it, but I never sit and say, “Wow, that’s an amazing shot. I took that.” For me, you’re always a student of nature. Nature is the perfect art, so you’re trying to do it justice. You’re trying to celebrate it, and sometimes you get an image worthy of the scene in front of you. It’s ongoing growth.

At what point did you know photography was more than just taking pictures?

Cristina: For me, it was early on. Photography has the power to captivate people’s attention. We are naturally curious as to how the image is made. What is the witchcraft that allows water to blur across a frame? I always thought it was easier to engage people’s attention to the important conversation about protecting nature.

When I first attended photography, seminars were male-dominated, and even within the nature photography realm, it was very action-oriented and competitive. Who has the best growling bear? Who got the best shot? I didn’t think about it that way. I really wanted it to be artistic, poetic, and captivating.

Paul: I was at the University of Victoria. I had all my scientific professors who are the world authority in their various fields, whether it’s salmon or, in this case, invertebrate life in British Columbia. I was diving and showed a few of my pictures to my professor, a world expert, post-doc with a Ph.D., and he was blown away.

My professor wasn’t a diver. He was drawing these animals for the class on a chalkboard. But my images could be of value to connect an underworld to the above world. You realize that very few people get to explore the ocean, and with a camera, you can bring the ocean to everyone.

Paul, what do you love that is uniquely Canadian, and what about being Canadian has shaped the person you’ve become?

Paul: I have a lot to be thankful for about my upbringing. I was shaped more by the Inuit of Baffin Island, which doesn’t get more Canadian. People have been living on and connected to the land for 20,000 years. When you grow up in a community where you’re one of three or four non-Inuit families, and you have no television, no radio, and your entire time is spent outside on the sea ice playing with your Inuit friends, you learn two things, A) survival skills, B) to develop the right-brain creative side of oral storytelling, visual storytelling, and drawing.

When I was 11, one of my drawings was in the Ottawa Museum of Civilization. I was sent there because I loved drawing and connecting visually with this incredible polar world. I’d say those two things shaped me the most, survival skills and being tough. I say the skill I’m better at than any photographer in the world is I’m better at freezing and being miserable. I’m good when you can’t feel your feet or hands, and you get frostbite. Your ears are frozen. Your cheeks are frozen. I’m in a happy place, still working through it all. I attribute a lot of that toughness to my Inuit friends, who taught me to suck it up and keep going, not only when diving under sea ice that is 10 feet thick and the water temperature is -1.5. You not only have to survive, you also have to create art, for some of the most discerning magazines in the world, like National Geographic.

Cristina, did someone in your family, in Mexico, inspire you to embark on this journey?

Cristina: Yes. I loved growing up in Mexico, and I love everything about Mexican culture and tradition and our history going back thousands of years. My father loved the ocean. He grew up in a coastal town in the coastal city of Tampico in the Gulf of Mexico. He’s the one who taught me how to swim in the ocean, how not to be afraid, but be respectful of the ocean. My mother is the one who is an artist.

She’s a painter, she plays guitar, and she’s always had this tremendous appreciation for the great Mexican artists, people like Alfaro Siqueiros or Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. We used to go to museums and visit their works of art, to take it in, and to be proud of being Mexican and having this incredible artistic heritage. She always encouraged that. Today, as a Mexican artist, I feel the weight of that responsibility to carry on with these Mexican traditions.

How do you stay grounded in your work when I’m sure you get very emotional seeing firsthand the beauty you encounter and the flip side – the perils of our planet and what lies beneath our waters?

Paul: Most people stand on the beach, look out at the ocean and see the sun reflecting on the water and think, “All is well in the world.” But when you put on a dive mask and lower your face an inch below the surface, you see a different world. You see ocean acidification, bleaching and dying coral reefs, a 95% decline in big fish, and 100 million sharks killed yearly.

Once you go down the path of caring for this planet, you carry a hefty weight on your shoulders. I think we stay grounded by being active. If we were inactive, we would get very down and depressed. We work tirelessly daily to connect the global audience to the most significant issues facing our planet and request people to come on a journey with us to help drive change.

The only way we can deal with our climate-global-ocean-Earth anxiety is by taking action. That’s what grounds us. What grounds me, from a humble point of view, is that I’m careful to tell my mother that even if I got my Honorary Doctorate yesterday, I’m reluctant to tell her because she’ll tell me I’m getting a big head. We all need that mother and that person in our lives to bring us back to Earth, and Cristina’s mother is the same way with her.

Of all the places you have traveled, in search of the perfect image, please tell us one of the places that stands out the most and why.

Cristina: Paul and I are very guilty of falling in love with every place we visit. Many years ago, I went to University in the Gulf of California and Northern Mexico and always wanted to return. As an artist, I wanted to return with Paul so he could see for himself this special place.

Several months ago, we arrived in Mexico on our boat, the SeaLegacy1. I don’t think we were ready for the abundance of life and the magnificence of the wildlife that lives in the Gulf of California because it’s been so overly exploited by the industrial fishing fleet. I was not expecting to encounter blue whales, 15 minutes away from the beach bar, millions of Mobula Rays jumping out of the water, and sharks. It was mind-blowing.

Paul: For me, it’s a no-brainer to think of South Georgia, Antarctica, where no animal is afraid of you. If you could design the perfect habitat for a wildlife lover, photographer, and artist, that would be it. You walk into the most beautiful canvas you’ve ever seen when you’ve got a backdrop of 9,000-foot mountains, knowing the history of Shackleton. To walk onto the beaches where there are 10,000 elephant seals and 10,000 fur seals. You walk up over a little rise and see 300,000 king penguins filling an entire valley floor stacked so tight. You sit down, and the second you do, animals come and sit on your lap, or baby elephant seals come and sleep against you. You can’t imagine. If there is a heaven, for me, it would be that. It would be that moment where you are immersed and surrounded by the most beautiful, charismatic megaphone on the planet. For me, it’s definitely South Georgia.

Cristina: The work we do aims to be a reminder that we do live on a beautiful planet that is worth protecting. But it’s more than that. It’s the spaceship carrying all of humanity across the universe, and the wildlife we share this planet with are our fellow passengers.

Do you meditate?

Paul: I meditate in nature, just by virtue of sitting on a mountaintop and looking out over vast expanses of land. My eyes are focused on looking for bears and animals. I enter a deep state of concentration. The most powerful journey I’ve ever been on was when I lived on the open barren lands for three months with just the wolves, bears, and musk oxen. I didn’t see another human for three months. It was like entering into a constant state of meditation. The physical aspect of walking 20 to 40 kilometers a day with a heavy pack, sitting there and looking day in and day out for wildlife, and the 24 hours of sunlight floating down these beautiful Arctic Rivers, you are in a constant state of meditation. It’s amazing how your senses become attuned to the environment around you.

It’s like becoming a wild animal. I could look up and see a wolf that’s five miles away running across the ridge line with my open eyes. I wouldn’t have been able to do that before with my pair of binoculars. You become like a wild animal. For me, that’s my favorite level. That’s the deepest state of meditation that I will enter. It’s definitely my church, my spiritual place. It’s where I feel connected to life and Earth and everything around me. It’s very, very powerful.

Cristina I would say it’s the same for me, and to add to that, the opportunity that is so remarkable that we both have to spend time in the company of Indigenous people that are still connected to the operating system of planet Earth. You learn to be in place differently, in a way that doesn’t see the world in nouns. Things are not nouns to be exploited. The tree, the bear, the whale, you learn to see it in verbs, how things work together.

The forest is alive because the salmon swim in the river because the bear forages for berries. So you learn to start seeing, like Indigenous people do, the ecosystem as a whole and not just in the parts that can be sold.

How do you inspire young children and young adults who want to pursue a career in photography to choose your line of work so that they will continue to tell the stories you are telling now about animals, nature, and sea life?

Paul: We both love mentoring and helping young photographers. The advice I have for young people now is very different from the advice I had, say, 10, 15 years ago when the whole goal of life was to make it into National Geographic as there was only that.

The chances of getting there were next to impossible, but if you did, your life was stressful but beautiful. Nowadays, young people will say, “I want to help. I want to do what you do.” I tell them that the photography world is very different today. The entire visual storytelling world is fascinating, and if they want to get involved in making a difference on this planet, then they need to become a great writer.

To have the gift of being a good listener, a storyteller, and a writer is the greatest gift. I tell them they need to be able to communicate on social media, shoot and edit videos, take pictures, and use pictures and videos to understand graphic arts and to understand marketing. When you think of many of the best scientists in the world on the frontlines of conservation, they may not be the best communicators as they have a significantly developed left brain. They’re looking at the world in numbers and math, and they can write scientific papers that will only be seen by a handful of their peers. If a young person with an incredibly diverse set of skills can communicate and transcend that and put that into the public media, they’ve added tremendous value for that scientist and ultimately, great value for storytelling and our planet. That’s how we encourage young people.

Cristina: Back in 2004, nature photography didn’t include any purpose in the action of taking photographs. I coined the term ‘conservation photography’ to get an active and purposeful art form to say taking photographs is not enough. If we want to change the world, we must make sure that those photographs are purposeful and seen by the people who can make decisions that change how we see the world.

The most valuable contribution I’ve been able to make is the idea of conservation photography. Today, so many thousands of young photographers find a compelling argument for getting involved in the profession to use their cameras as a tool to shine a light on the importance of protection.

In 2005, we built the International League of Conservation Photographers to provide a platform for photographers on environmental issues.

How do you find the right collaborators?

Cristina: There are a couple of kinds of collaboration. Our work, especially the work we do with SeaLegacy, is very much intended to benefit the conservation partners with whom we work. We look for smaller organizations that cannot afford to hire a team of the best photographers and filmmakers in the world but need the type of impact media we create to move the needle on whatever issues they’re working with. We look for people that are working on the frontlines all over the world.

We currently have partners in Panama, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Mexico. Our plan with our boat, the SeaLegacy1, is to travel around the world and then working on the front-lines with our partners. As for our team, we need people that subscribe to the idea that storytelling is valuable. For many people, it’s hard to wrap their heads around the intrinsic value of convening around a story because it sounds far-fetched, Still, it is undeniably powerful. It builds constituencies that support what ministers, and decision-makers need to change the colonial legacy legislation that is very destructive to our planet.

What will it take for the curriculum in schools to include a lot more about our oceans?

Cristina: Understanding the operation of our planet, as if it’s a spaceship and we need to understand how to fly it, is a priority. Instead, from the time we are in school, we are taught how to exploit it. You study to become an engineer to find ways to exploit, not protect. It’s a mindset that needs to shift completely. Every person that lives on this planet is an operator of the spaceship, and we need to understand how it works.

Paul: I was the main climate photographer for National Geographic about 21 years ago. At the time, I couldn’t get a scientist to go on record to even say the words ‘climate change.’ When I was on a lecture tour in 2004 and 2005, I was asked to ease up on the word ‘climate change’ as it would upset the audience.

The fact that we’re all talking about climate change now and about the loss of coral reefs, we are moving in the right direction. The problem is that nowadays, we are inundated with noise with social media. At times it’s as if Science almost doesn’t matter. It becomes about everyone’s opinions. Also, world leaders play a big part as they can have a serious impact by accepting Science or dismissing it.

How do we rally adults and government who will not listen to the facts?

Cristina: We believe that the power of the people is greater than the people in power. If we can galvanize inspiration, passion, and then action, on behalf of our planet in all corners of the world, to push the people in power to make the decisions that we, the people, demand of a living planet, that’s the purpose of our work.

We focus a lot of our effort on creating action in young people coming of age to vote and demand the change we need in the next ten years. We don’t have any more time. We have to focus on all of it now.

Where do you feel most at home and in your comfort zone?

Cristina: At home in Nanoose Bay, British Columbia.

Paul: Diving and disappearing for two hours underwater to sit with the fish. That’s where I’m most at home.

What do you eat when you’re on expeditions?

Cristina: We keep it simple. We eat a lot of grains. On the boat, we have a storage of fresh vegetables. We have a bilge where you can keep stone fruit and root vegetables for a long time. We found this farm that does freeze-dried vegetables. They last forever in sealed cans, and then they’re restored with water and last for years, and they’re delicious.

Paul: I wouldn’t say we’re vegan or vegetarian, but we’re massive reducetarian.

What is the solution to the growing demand for seafood and overfishing?

Cristina: The wild stocks of fish that are left in the ocean should be left there because they’re part of the carbon cycle that keeps our planet alive. The food that’s necessary for people to survive– and the fish in the ocean should also be available to coastal communities with no other options.

The rest of us who have an option should eat a lot lower in the food chain. There should be enormous investments in the right aquaculture technology to grow fish, not in ocean pens, where they pollute. They breed parasites and viruses, but in land-based facilities where the water is treated and not returned to the ocean or polluted and contaminated and where we’re not feeding aquaculture fish with more ocean fish and wild fish. We need to figure out the aquaculture bit in a way that doesn’t destroy the ocean.

Paul: When you think about it, at an Atlantic salmon fish farm, originally brought in because we thought it was a healthy solution, it takes anywhere from two to four pounds of wild fish to make one pound of farm fish. When you have hundreds of millions of pounds of farm fish growing worldwide every year, that’s maybe a billion pounds of wild fish in the form of anchovies and herring, which is also used for chicken feed.

There are many innovative companies making great strides in sustainable aquaculture. What’s being done in this sector is a big part of the solutions we need.

What do you want our readers to know about SeaLegacy.org, which you co-founded in 2014?

Paul: I go back to the phrase Cristina and I keep saying, that ‘the power of the people is greater than the people in power.’ If you’re sitting there frustrated, scared, and helpless, the strength of SeaLegacy.org is a convening spot. We will provide the campaign, purpose, and call to action. We’re only as effective as people willing to come and get involved, whether it’s lending a small dollar donation, sharing on social media, or something as simple as talking to the principal at school and demanding they no longer use plastic.

This world is ours. It’s not up to us to save the world. It’s up to all of us collectively to work together. Everyone has petition fatigue, but when you go to SeaLegacy.org or our social media, you will see that we’ve had many incredible wins through petitions. For example, we were just able to ban the mile-long death nets off the coast of California because of the power of the people. We were able to get 125,000 signatures. These mile-long nets kill turtles, dolphins, and whales indiscriminately through the night.

People need to get involved and open themselves up to becoming active in the conservation movement.

Please tell us why fishing for Swordfish creates this huge problem for other marine life?

Paul: There is high demand for Swordfish in restaurants, but it’s a hard fish to catch on hook and line, so they use nets that are a mile long and about 100 feet deep. They cast them out at night, and they sit there all night. In a mile-long net, anything swimming by gets caught in it and tied. When you swim along with these nets, you see Thresher Sharks, Mako Sharks, Great Whites, Mobula rays, Stingrays, and a ton of Dolphins.

They’re supposed to report all this bycatch, but we have, through our partners, The Turtle Island Restoration Network and Mercy For Animals, put observers on board and were able to film and witness the illegal sinking of Dolphins and to see Gray Whales dead wrapped up on a beach in nets, and Sea Lions dead in the nets. It’s really sad. By the time a slab of Swordfish arrives on your plate, you have no idea you’re a part of this problem. If you like to see this video and more please visit our YouTube channel the video called The Death Nets. It’s horrific, gross, and terrifying. But it’s that powerful visual storytelling that was able to push this over the edge and get this banned.

You said on your website that you fail 98% of the time. Can you please explain what you mean by that?

Paul: When I wake up in the morning and say, ‘I’m going to go shoot the most powerful image for the most discerning magazine in the world,’ there’s a 98% chance that I’m going to fail. I did a wolf story for National Geographic, which took over three months, and I only saw wolves for five days. I only photographed them for three days, and I only had two good days of shooting out of those 90 days. That’s a typical shoot.

Special Thank you to:

Cristina Mittermeier & Paul Nicklen, and the crew onboard the SeaLegacy1 for capturing images of the life onboard.

Many of Paul and Cristina’s images are shown here

are available as limited edition prints at:

Comments